So, it's been a while.

A Preamble, but an Important One

I've been busy, largely with uni work really, but I've also just been spending a lot of my time grinding the hell out of Super Smash Bros. Melee. I'm sure I'll end up writing a lot about that game in the future, you're welcome in advance.

In my hours grinding Slippi unranked, ledgedashes and dashbacks out of crouch, though, I knew there was something that needed addressing, being the reason I stopped playing and following Smash as a series altogether for a few months around July. What eventually brought me back (on top of my general love for the series), and more towards Melee as well, was me more clearly processing the set of events that acted as a trigger point for me to want to disassociate with that community.

Super Smash Bros. Melee is a platform fighting game released for the Nintendo GameCube in 2001. It, alongside the most recent entry into the series Super Smash Bros. Ultimate have comprised a lot of how I'd spend my time in one way or another since late 2018, whether it'd be practicing, playing with my brothers and friends, watching community content or, most notably, watching tournaments. I think the series at a high level - and personally I think this is more pertinently so with Melee - is some of the most riveting and exciting competition out there.

This is all beside the point though.

For the uninitiated, over the course of July, and later on in the year as well, the Super Smash Bros. community on both sides, Melee and Ultimate (though debatably moreso with the Ultimate crowd) have come forth with a whole host of allegations ranging from rape, to other forms of sexual assault and harrassment, to grooming of minors, to general abuse of power, to - you name it, it probably came out. A Kotaku article on the matter claims that over 50 of these came out, just to give you a sense of scale, of what is in truth, a relatively small community.

My knee-jerk reaction, what my manas would say if you're into yogic philosophy, was a concoction of all the negative emotions you could think of, but while there were notes of sadness that large community figures had done awful things, the overwhelming sensation was disgust, vehement anger, disappointment and compassion towards the victims. The community as a whole had a different reaction, which is what I actually wanted to talk about here.

Idolisation

Arguably, the two most notable figures in the Smash community who had allegations made against them were ZeRo and Nairo, at the time two of the biggest content creators in the Smash Ultimate community and who would both rank highly on the GOAT lists of post-Melee games. Now, something to bear in mind is that the Smash community, especially the Ultimate community, is an extremely young one, not in the sense that it's new, but in the sense that its player-base is largely children - people who haven't fully understood the ramifications of just how bad some of these accusations, if true, really are. And once the respective parties had both come out with statements confirming the accusations in one way or another, On a sidenote, Nairo has made a statement recently after consulting his lawyers denying the accusations to a large extent, and will take his accuser to court over the issue, but this is unrelated to the point of this entry. there were somehow still fans coming to their defence, pleading for them to return to the community, saying they knew they were good people and that grooming and statutory rape were just small mistakes that they had made, and they had grown from them.

I mean, needless to say, this infuriated me.

A significant portion of the community's response to some of these allegations had no sympathy for people who could have been exposing their own trauma to the world, even going so far as to accuse almost all of them of clout-chasing. And there's other aspects to these events that need addressing, but my mind was stuck on one question: why? Why defend these people, especially after they've come forward confirming the allegations?

Because Nairo has a sick Palutena? Because they make funny content on YouTube and Twitch? How do people become emotionally attached to these people who they don't know personally, when those who know them personally have come forward and denounced their actions?

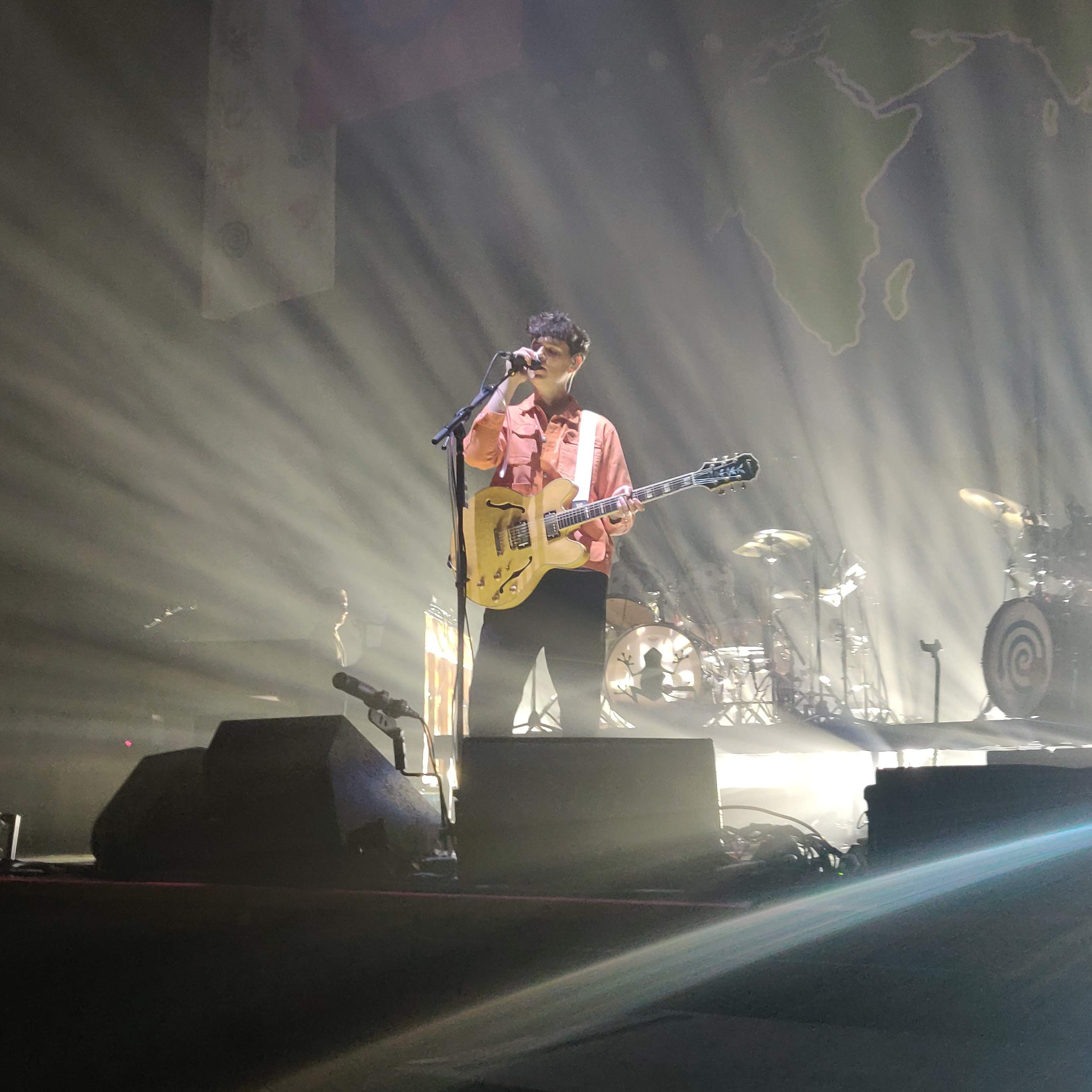

It's something that I've never gotten my head around. Sure, I've gotten attached to the content people have made, I closely follow artists to the point of reading their biographies, but I've never formed a parasocial connection with anyone, at the very least not since reaching adolescence. So with Will Toledo, as much as I'm a massive fan of his body of work, even his personality online, it's constantly in the back of my mind that his personal life is none of my business, and should an allegation be brought to light against him, of course I'd give it the time of day that it would warrant.

It's at the point now, where streamers like Ludwig, who initially came out of the Melee scene, has to tell people that he isn't their friend. Where Leffen, a very controversial figure in Melee, has to constantly tell people that you don't know anyone, even if you've watched hours of their gameplay.

This aspect of fandom is why I avoid saying I'm a fan of someone, as opposed to saying I enjoy consuming their work. Because you don't know them. You know a sliver of their personhood that they choose to project to the world. Hell, even with the people you do know, you only know how they act around you and the others you know.

I stopped calling myself a K-pop fan around 2017. The nature of the fandom required personal, emotional and financial investment into a group of people who produced stage performances, music and variety shows. My experience with K-pop was a large part in empathising with people who idolise others with whom they have no personal connection whatsoever. Considering how much time and money you inevitably end up pouring into supporting your favs, of course people end up creating emotional investments, dreaming of being in a relationship with one idol or another. Even the name for the celebrity implies it. So when it turns out Seungri is a total piece of shit or Irene is acts awfully towards her stylists and backup dancers, fans are more quick to forgive them than the victims are.

It can be difficult, but the pits that are celebrity worship, idolisation and parasocial relationships demand discipline in consumption, especially in the social media and content-centric world we live in now. And people who don't exercise it could end up making the world a less safe place.

Don't idolise, folks.